auth. Paul Fang Founder of Fashion Exchange & Suntchi

112 years ago, back in 1911 during the eruption of the Xinhai Revolution in China, a young professor, aged merely 28, brought up the seminal innovation theory in his first well-known work, stating that “carrying out innovations is the only function which is fundamental in history”. He also accented that it is entrepreneurship that ”replaces today’s Pareto optimum with tomorrow’s different new thing”. This young visionary was none other than Joseph Schumpeter. Later on, he spent 18 years teaching at Harvard University, where he nurtured the minds of three future Nobel laureates in economics. Schumpeter is also credited as the pioneer who first introduced terms and concepts such as innovation, entrepreneurial spirit, creative destruction, strategy, and venture capital. Inspired by Schumpeter’s ideas, Clayton Christensen crafted works like The Innovator’s Dilemma, introducing the notion of “creative destruction”. Michael Porter built upon Schumpeter’s early advocated “strategy” with his work Competitive Strategy. Peter Drucker, celebrated as the “father of modern management”, paid homage to Schumpeter in his book Innovation and Entrepreneurship, recognizing Schumpeter as the only modern economist who concerned himself with the entrepreneur and the impact of entrepreneurship on the economy. (1)

Schumpeter categorized entrepreneurs’ innovation into five types: 1. launch of a new product or a new species of already known product; 2. application of new methods of production, sales, or marketing of a product (not yet proven in the industry); 3. opening of a new market (the market for which a branch of the industry was not yet represented); 4. acquiring of new sources of supply of raw material or semi-finished goods; 5. new industry structure such as the creation or destruction of a monopoly position. This passage later became widely quoted, with some succinctly summarizing it as product innovation, technological innovation, market innovation, resource allocation innovation, and organizational innovation. These concepts may seem commonplace today because they have long served as the cornerstone of all innovation theories. However, it’s important to note that Schumpeter proposed these ideas as early as 1911.(2)

The FASHION IP 100 and the Global Fashion IP White Paper, released for five consecutive years, place a significant spotlight on fashion IPs, notably represented by fashion designers, artists, celebrities, and influencers. The focus lies in exploring the models, methods, and cases in which brands launch new products, create new scenarios, and attract new customers through crossover collaborations with fashion IPs. At its essence, this echoes Schumpeter’s theory of innovation: innovation is not about invention; rather, it’s about creating value through the “new combinations” of diverse production factors or resources. Fashion IPs and partner brands bring together different ideas, creativity, elements, styles, materials, and technologies in new combinations to create innovative products or even cultural phenomena that embody the latest trends. Whether through limited production to evoke scarcity or by crafting “familiar surprises” to ignite popularity, these initiatives generate positive reviews and sales in the market, creating value for consumers, partners, and businesses simultaneously. This follows the typical innovation activity curve outlined by Schumpeter. Fashion IPs serve as the “brain” of innovation, acting as both creators and, much like entrepreneurs, essential catalysts driving the pulse of innovation activities. The vast majority of collaborations we witness in today’s market are largely centered around innovating products and markets. Despite several major industrial revolutions shaping human society and propelling progress and development, the fundamental nature of innovation has stayed constant. The only changes lie in the elements, resources, and the diverse ways they are combined. What we engage in today is essentially a homage to and practical application of the innovation theory pioneered by Schumpeter over a century ago.

In 1972, a 23-year-old youth graduated from the School of Political Science and Economics, Waseda University. After working for a few months in Tokyo, he returned to his hometown, Ube City in Yamaguchi Prefecture, where he took the reins from his father, inheriting a men’s suit store named “Ogori Shoji”. In 1984, at the height of Japan’s economic boom, he made a bold shift to steer away from pricey suits and opened his first store in the heart of Hiroshima, specializing in affordable casual wear made from high-quality fabrics. In 1991, amidst the collapse of the bubble economy in Japan, while many companies were closing down, he, at 42, defied the trend by proposing a plan to open 30 stores in a single year and rebranding the company as “Fast Retailing”. This enterprising individual was none other than Tadashi Yanai. Fast forward 32 years to October 12, 2023, when Fast Retailing unveiled its financial performance report for the fiscal year 2023 (ending in August 2023). The eight brands under its umbrella, including Uniqlo, achieved record-breaking results, with sales reaching 2.77 trillion yen and operating profits surging by 28.2% year on year to 381 billion yen (approximately $2.54 billion). Concurrently, the company’s stock price soared by 31%, elevating Tadashi Yanai’s fortune to $35.4 billion and securing his position as Japan’s wealthiest individual again on Forbes’ 2023 list of Richest Man in Japan.

The world is teeming with clothing brands, and there is an abundance of casual wear brands with diverse styles and positioning. Prior to Uniqlo, there was Gap, the most successful American casual wear giant worldwide. However, Uniqlo has managed to stand out by providing high-quality casual wear that is both stylish and highly affordable. Their products cater to a diverse group of people from different countries, ages, and skin colors, making it a daily essential for many. Additionally, Uniqlo can often create hot-selling items. This prompts us to wonder: why Uniqlo? Why is it Tadashi Yanai who leads this company to success? What adds to the intrigue is that the company’s inception, acceleration, and sprint occurred during the entirety of Japan’s “Lost 30 Years”, a period marked by the collapse of the bubble economy, economic downturn, business failures, and sluggish consumer spending. Over these 3 decades, nominal wages (unadjusted for inflation) in Japan saw a meager 4% increase, in contrast to the substantial 145% increase in the United States during the same period.

“Compared to brands at the forefront of fashion trends, Uniqlo excels in harnessing innovative technology, seamlessly blending design and quality to make each garment affordable, durable, and still in vogue,” says Tadashi Yanai, “Unless we do the right thing, the company won’t thrive, and employees won’t be happy. I refer to it as a pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty, namely embracing authenticity, altruism, and aesthetic awareness, both subjectively and objectively, in the creation of clothing.”(3)

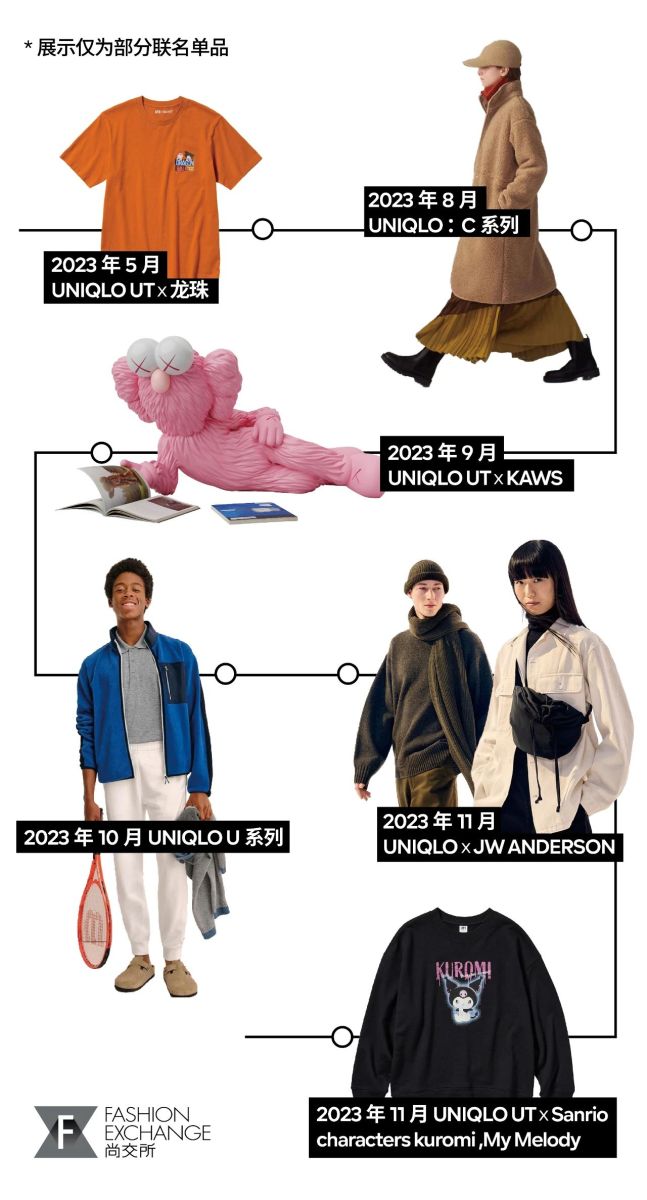

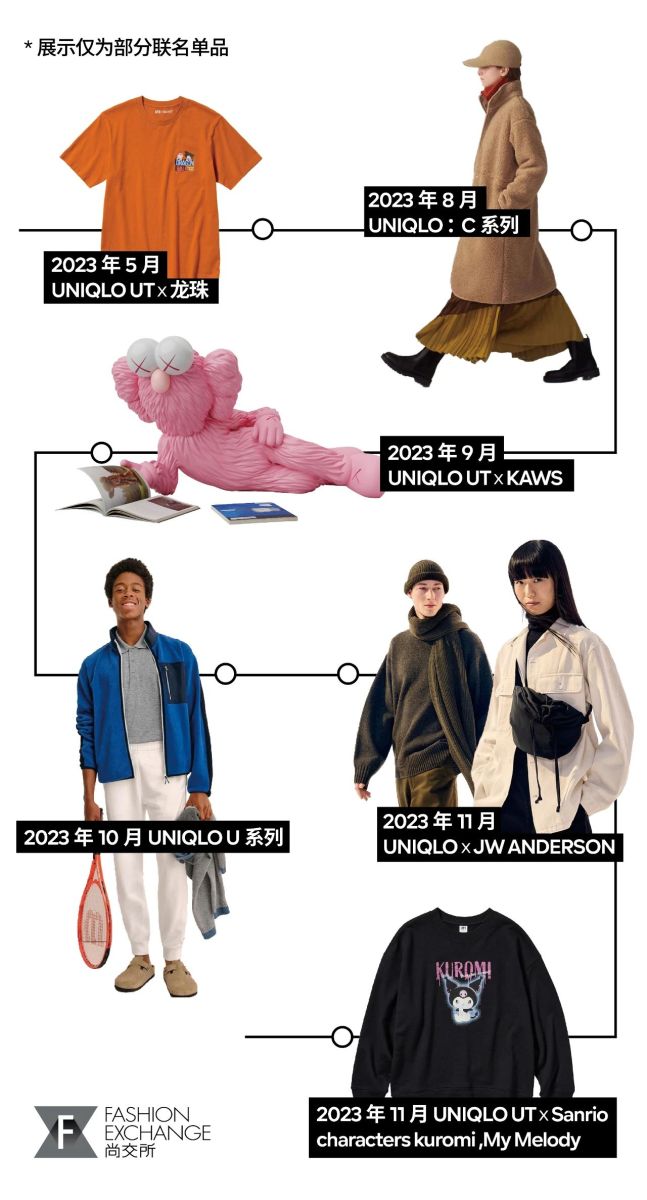

Tadashi Yanai’s actions spoke volumes in line with his words. Uniqlo’s initial triumphs were grounded in the harmonious blend of low prices and high-quality materials. In 1998, Uniqlo’s debut store in Tokyo unleashed a sensation with a lightweight wool sweater priced at a mere 2,000 yen, resonating strongly in the frugality wave of the post-bubble economy, with one in every four Japanese consumers making a purchase. Thereafter, Uniqlo continued its innovative journey in utilizing premium fabrics across different scenarios. The launches of their fleece collection, Ultra Light Down collection, Heat-Tech innerwear, and more all achieved significant success. This enduring success can be attributed to Tadashi Yanai’s unwavering commitment to exploring novel fabrics and integrating product quality, fashion, and functionality. In 2003, Uniqlo introduced the UT collection, and in 2013, NIGO took on the role of Creative Director for the UT line. Over the past two decades, UT has been dedicated to discovering and embracing popular culture elements that resonate with young people, spanning movies, manga, animation, art, and music. They’ve partnered with classic cartoon characters like Disney’s and Minions, cultural and artistic IPs like SPRZ, LEGO, MOMA, and the Louvre, as well as globally renowned artists and creators such as JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, ANDY WARHOL, KEITH HARING, Yayoi Kusama, JEFF KOONS, and KAWS. UT has also brought the younger generation back into a world of diverse game and anime IPs, including Demon Slayer, Dragon Ball, Naruto, Gundam, Star Wars, Saint Seiya, Super Mario, and Nintendo. With biannual releases of numerous crossover collaborations, UT has transcended the realm of a mere T-shirt to become a pioneer of global culture.

Regarding collaborations with designers, Uniqlo’s strategy has been marked by long-term projects and small, seasonal ventures. The former type includes the pioneering +J collection initially introduced in 2009 in collaboration with German designer Jil Sander, which made a comeback in 2020 for a second collaboration. There’s also the enduring collaboration with Ines de La Fressange, the muse of Chanel, which has spanned a decade, with 20 seasons since its debut in 2014. The U collection, a highly acclaimed collaboration with Christophe Lemaire, former artistic director of women’s wear at Hermès, initiated in 2016, continues to captivate audiences. The partnership with British fashion brand J.W. Anderson starting in 2017 is also still ongoing. The latest addition to this impressive lineup is the UNIQLO: C collection, inaugurated in 2023 in collaboration with Clare Waight Keller, former creative director of Chloé and Givenchy. Alongside these flagship collaborations, Uniqlo has also delved into smaller-scale and seasonal projects with designers such as Alexander Wang, Marni, White Mountaineering, and Marimekko. Over the past 15 years, Uniqlo's global market expansion has captivated consumers and propelled the brand's performance to new heights. The driving force behind this success lies in the implementation of an innovative strategy centered around collaborations and partnerships with fashion IPs.

As per Schumpeter’s framework, Uniqlo and Tadashi Yanai epitomize true “innovators” and typical “creative destructors”, consistently destructing old structures and perpetually creating new ones. By defying the traditional “impossible triangle” in the fashion industry—offering high-quality and fashionable designs with affordable prices—they’ve made their brand accessible to the masses while still appealing to the elite. Over the past 32 years, Tadashi Yanai has, perhaps even unbeknownst to himself, diligently put into practice all the five innovation types summarized by Schumpeter. Through collaborations with upstream raw material suppliers, globally renowned designers, and creative minds, and engaging diverse circles, including anime and cultural IPs, as well as close cooperation with manufacturing partners in Vietnam, Myanmar, and China, Uniqlo has harnessed the winds of globalization and seized the burgeoning opportunities in the Asian market, particularly in China, achieving contrarian success during Japan's "balance sheet recession". Leveraging innovations in product, technology, market, resource allocation, and organization, Uniqlo has become what it is today in defiance of economic challenges. According to an incomplete tally, spanning from 2013 to 2023, Uniqlo has collaborated with 38 designers, 72 artists, and over 270 cultural or anime IPs, resulting in more than 350+ co-branded collections or individual items. Over this period, from the fiscal year 2013, when sales already reached a remarkable 1.14 trillion yen, to the fiscal year 2023, there has been an astounding nearly 2.5-fold increase in sales and a remarkable 320% growth in profits. The expansion is further exemplified by the progression from 29 domestic stores in Japan in 1991 to a global network of 2,434 stores by 2023. The growth in sales and net profits over these 32 years is truly awe-inspiring. Time, as the witness, reflects Uniqlo's unwavering commitment to innovation. This narrative holds valuable insights and inspiration for Chinese entrepreneurs navigating the challenges of a globalized yet fragmented landscape, coupled with slowing economic growth and intense competition.

In pioneering new markets through innovation, Apple stands out as an excellent representative. While Nokia dominated the traditional mobile phone market, Apple introduced the smartphone, fundamentally revolutionizing the entire industry. In an article titled What would Joseph Schumpeter have made of Apple?, the author argues that Apple embodies many aspects of the concept of “creative destruction” proposed by Schumpeter. Similarly, in the fashion realm, Uniqlo is another outstanding example that demonstrates various features of “creative destruction”. Interestingly, Tadashi Yanai once remarked, “Our competitors are not fast-fashion brands like Gap or ZARA; our competitor is Apple.” Rather than considering them as competitors, it reflects a shared dedication to innovation, a keen understanding and anticipation of consumer needs, and a drive to overturning traditional norms. The two share a strong resemblance and a mutual admiration for their persistent pursuit of innovation.

Uniqlo believes that clothing is not just about fashion but is fundamentally a necessity in life, encapsulated in their philosophy of LifeWear. Breaking it down, it signifies the fusion of “Life” and “Wear”, representing high-quality everyday apparel perfect for daily dressing. What sets Uniqlo apart is its astuteness in elevating design and creativity to the strategic forefront of corporate competition, much like Steve Jobs did. Simultaneously, Uniqlo spares no effort in enhancing product quality, durability, and added value through the innovation of fabric technologies. Similar to the iterative approach of Apple’s iPhones, Uniqlo’s collaborative collections maintain its foundational products' core features and brand style while focusing on upgrading and enriching key technologies and details. Leveraging the influence of renowned designers, Uniqlo enhances brand strength, tapping into markets where both the elite and fashion-conscious consumers are willing to invest. Christophe Lemaire has emphasized the significance of the “KISS principle”, which stands for “Keep it Simple, Stupid”. In his view, excellent products should cater to everyone, whether young individuals immersed in fashion culture or the general public, making products easily understandable and acceptable to all through the simplest intuition. This principle is highly applicable to other industries and brands aspiring to excel in "product innovation".

Regarding collaborations with globally renowned designers, Yukihiro Katsuta, Group Senior Executive Officer at Fast Retailing and Head of Global Research and Development at Uniqlo, believes that designers with diverse backgrounds can bring unique perspectives to brand design. He sees the challenge for the brand itself as learning how to understand various ways of thinking and adopting new working methods within the entire system. “We always believe that there is room for improvement, and there are many things we should and can do. Perhaps it’s difficult to achieve solely on our own, and maybe we need more support and need to learn from others. This is why designer collaborations are not just for commercial purposes but also for market goals. It’s an investment in the company’s future.”(4)

Uniqlo is not alone on the journey of innovation and creative destruction. There are other industry players also adopting similar innovative strategies and consistently experiencing growth. Some notable examples include Nike, born in Portland, USA, in 1972; Decathlon, founded in France in 1976; Crocs, born in America in 2002 and turned into a global sensation with its “ugly clogs"; Moncler, founded in France in 1952 and acquired by Italian entrepreneur Remo Ruffini in 2003; UGG, founded in 1978 in Southern California and later acquired by Deckers in 1995…This trend is even more pronounced in the luxury industry, where the importance of creativity, innovation, and collaboration cannot be overstated. Over the past decade, many luxury brands have appointed non-traditionally trained creative directors, engaging in diverse collaborations with trendsetting brands, contemporary artists, pop culture icons, local cultures & intangible cultural heritage, digital technologies, and the metaverse. Noteworthy mentions include Louis Vuitton, Dior, Gucci, Balenciaga, Fendi, Bvlgari, Tiffany&Co., Prada, Miu Miu, Loewe, and others. However, the proliferation of such collaborations raises a question: when innovation itself loses its novelty, it becomes a call for fresh waves of innovation and creative destruction to break through the old equilibrium or monopoly.

Tadashi Yanai’s office hangs a piece of calligraphy that reads, “Success often comes during tough times, while failure arises from arrogance.” He mentions that Sam Walton’s Made in America and Peter Drucker’s Innovation and Entrepreneurship have had a deep and lasting impact on him. (5)

Anyone who acknowledges innovation as the fundamental driving force of economic development can be referred to as a “Schumpeterian”. In this sense, Tadashi Yanai and his fellow explorers may well be considered as such. Through his own experiences and achievements, he has exemplified the integration of theories and practices, demonstrating how Uniqlo can navigate the cycles and achieve rejuvenation and growth amidst Japan’s “Lost 30 Years” through Schumpeter’s principles of product innovation, technological innovation, market innovation, and organizational innovation. This has allowed Uniqlo to surpass American brand Gap and catch up with H&M from Sweden and ZARA from Spain, with the ultimate goal of becoming the world’s number one brand. However, despite this success, Tadashi Yanai humbly refers to it as “One Win, Nine Failures”.

Understanding this perspective holds practical relevance for our present day.

References:

(1)/(2). “Why Are Innovators Considered Schumpeterians?” - LatePost

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/FJF1SEvk1zsEbo42olTEYQ

“The Theory of Economic Development” by Joseph Schumpeter, translated by Jia Yongmin, China Renmin University Press, 2019 edition, P61.

(3)/(5). “Uniqlo Founder Tadashi Yanai: Running a Business Requires Making Everyone Around Happy” - iBloomberg

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/Ke3ieXV3PUsDsLx-B7_gIg

(4). “Uniqlo’s Plan C” - iBloomberg

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/dg0DpA7IyXGYUYjWzWzKvg

auth. Paul Fang Founder of Fashion Exchange & Suntchi

112 years ago, back in 1911 during the eruption of the Xinhai Revolution in China, a young professor, aged merely 28, brought up the seminal innovation theory in his first well-known work, stating that “carrying out innovations is the only function which is fundamental in history”. He also accented that it is entrepreneurship that ”replaces today’s Pareto optimum with tomorrow’s different new thing”. This young visionary was none other than Joseph Schumpeter. Later on, he spent 18 years teaching at Harvard University, where he nurtured the minds of three future Nobel laureates in economics. Schumpeter is also credited as the pioneer who first introduced terms and concepts such as innovation, entrepreneurial spirit, creative destruction, strategy, and venture capital. Inspired by Schumpeter’s ideas, Clayton Christensen crafted works like The Innovator’s Dilemma, introducing the notion of “creative destruction”. Michael Porter built upon Schumpeter’s early advocated “strategy” with his work Competitive Strategy. Peter Drucker, celebrated as the “father of modern management”, paid homage to Schumpeter in his book Innovation and Entrepreneurship, recognizing Schumpeter as the only modern economist who concerned himself with the entrepreneur and the impact of entrepreneurship on the economy. (1)

Schumpeter categorized entrepreneurs’ innovation into five types: 1. launch of a new product or a new species of already known product; 2. application of new methods of production, sales, or marketing of a product (not yet proven in the industry); 3. opening of a new market (the market for which a branch of the industry was not yet represented); 4. acquiring of new sources of supply of raw material or semi-finished goods; 5. new industry structure such as the creation or destruction of a monopoly position. This passage later became widely quoted, with some succinctly summarizing it as product innovation, technological innovation, market innovation, resource allocation innovation, and organizational innovation. These concepts may seem commonplace today because they have long served as the cornerstone of all innovation theories. However, it’s important to note that Schumpeter proposed these ideas as early as 1911.(2)

The FASHION IP 100 and the Global Fashion IP White Paper, released for five consecutive years, place a significant spotlight on fashion IPs, notably represented by fashion designers, artists, celebrities, and influencers. The focus lies in exploring the models, methods, and cases in which brands launch new products, create new scenarios, and attract new customers through crossover collaborations with fashion IPs. At its essence, this echoes Schumpeter’s theory of innovation: innovation is not about invention; rather, it’s about creating value through the “new combinations” of diverse production factors or resources. Fashion IPs and partner brands bring together different ideas, creativity, elements, styles, materials, and technologies in new combinations to create innovative products or even cultural phenomena that embody the latest trends. Whether through limited production to evoke scarcity or by crafting “familiar surprises” to ignite popularity, these initiatives generate positive reviews and sales in the market, creating value for consumers, partners, and businesses simultaneously. This follows the typical innovation activity curve outlined by Schumpeter. Fashion IPs serve as the “brain” of innovation, acting as both creators and, much like entrepreneurs, essential catalysts driving the pulse of innovation activities. The vast majority of collaborations we witness in today’s market are largely centered around innovating products and markets. Despite several major industrial revolutions shaping human society and propelling progress and development, the fundamental nature of innovation has stayed constant. The only changes lie in the elements, resources, and the diverse ways they are combined. What we engage in today is essentially a homage to and practical application of the innovation theory pioneered by Schumpeter over a century ago.

In 1972, a 23-year-old youth graduated from the School of Political Science and Economics, Waseda University. After working for a few months in Tokyo, he returned to his hometown, Ube City in Yamaguchi Prefecture, where he took the reins from his father, inheriting a men’s suit store named “Ogori Shoji”. In 1984, at the height of Japan’s economic boom, he made a bold shift to steer away from pricey suits and opened his first store in the heart of Hiroshima, specializing in affordable casual wear made from high-quality fabrics. In 1991, amidst the collapse of the bubble economy in Japan, while many companies were closing down, he, at 42, defied the trend by proposing a plan to open 30 stores in a single year and rebranding the company as “Fast Retailing”. This enterprising individual was none other than Tadashi Yanai. Fast forward 32 years to October 12, 2023, when Fast Retailing unveiled its financial performance report for the fiscal year 2023 (ending in August 2023). The eight brands under its umbrella, including Uniqlo, achieved record-breaking results, with sales reaching 2.77 trillion yen and operating profits surging by 28.2% year on year to 381 billion yen (approximately $2.54 billion). Concurrently, the company’s stock price soared by 31%, elevating Tadashi Yanai’s fortune to $35.4 billion and securing his position as Japan’s wealthiest individual again on Forbes’ 2023 list of Richest Man in Japan.

The world is teeming with clothing brands, and there is an abundance of casual wear brands with diverse styles and positioning. Prior to Uniqlo, there was Gap, the most successful American casual wear giant worldwide. However, Uniqlo has managed to stand out by providing high-quality casual wear that is both stylish and highly affordable. Their products cater to a diverse group of people from different countries, ages, and skin colors, making it a daily essential for many. Additionally, Uniqlo can often create hot-selling items. This prompts us to wonder: why Uniqlo? Why is it Tadashi Yanai who leads this company to success? What adds to the intrigue is that the company’s inception, acceleration, and sprint occurred during the entirety of Japan’s “Lost 30 Years”, a period marked by the collapse of the bubble economy, economic downturn, business failures, and sluggish consumer spending. Over these 3 decades, nominal wages (unadjusted for inflation) in Japan saw a meager 4% increase, in contrast to the substantial 145% increase in the United States during the same period.

“Compared to brands at the forefront of fashion trends, Uniqlo excels in harnessing innovative technology, seamlessly blending design and quality to make each garment affordable, durable, and still in vogue,” says Tadashi Yanai, “Unless we do the right thing, the company won’t thrive, and employees won’t be happy. I refer to it as a pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty, namely embracing authenticity, altruism, and aesthetic awareness, both subjectively and objectively, in the creation of clothing.”(3)

Tadashi Yanai’s actions spoke volumes in line with his words. Uniqlo’s initial triumphs were grounded in the harmonious blend of low prices and high-quality materials. In 1998, Uniqlo’s debut store in Tokyo unleashed a sensation with a lightweight wool sweater priced at a mere 2,000 yen, resonating strongly in the frugality wave of the post-bubble economy, with one in every four Japanese consumers making a purchase. Thereafter, Uniqlo continued its innovative journey in utilizing premium fabrics across different scenarios. The launches of their fleece collection, Ultra Light Down collection, Heat-Tech innerwear, and more all achieved significant success. This enduring success can be attributed to Tadashi Yanai’s unwavering commitment to exploring novel fabrics and integrating product quality, fashion, and functionality. In 2003, Uniqlo introduced the UT collection, and in 2013, NIGO took on the role of Creative Director for the UT line. Over the past two decades, UT has been dedicated to discovering and embracing popular culture elements that resonate with young people, spanning movies, manga, animation, art, and music. They’ve partnered with classic cartoon characters like Disney’s and Minions, cultural and artistic IPs like SPRZ, LEGO, MOMA, and the Louvre, as well as globally renowned artists and creators such as JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, ANDY WARHOL, KEITH HARING, Yayoi Kusama, JEFF KOONS, and KAWS. UT has also brought the younger generation back into a world of diverse game and anime IPs, including Demon Slayer, Dragon Ball, Naruto, Gundam, Star Wars, Saint Seiya, Super Mario, and Nintendo. With biannual releases of numerous crossover collaborations, UT has transcended the realm of a mere T-shirt to become a pioneer of global culture.

Regarding collaborations with designers, Uniqlo’s strategy has been marked by long-term projects and small, seasonal ventures. The former type includes the pioneering +J collection initially introduced in 2009 in collaboration with German designer Jil Sander, which made a comeback in 2020 for a second collaboration. There’s also the enduring collaboration with Ines de La Fressange, the muse of Chanel, which has spanned a decade, with 20 seasons since its debut in 2014. The U collection, a highly acclaimed collaboration with Christophe Lemaire, former artistic director of women’s wear at Hermès, initiated in 2016, continues to captivate audiences. The partnership with British fashion brand J.W. Anderson starting in 2017 is also still ongoing. The latest addition to this impressive lineup is the UNIQLO: C collection, inaugurated in 2023 in collaboration with Clare Waight Keller, former creative director of Chloé and Givenchy. Alongside these flagship collaborations, Uniqlo has also delved into smaller-scale and seasonal projects with designers such as Alexander Wang, Marni, White Mountaineering, and Marimekko. Over the past 15 years, Uniqlo's global market expansion has captivated consumers and propelled the brand's performance to new heights. The driving force behind this success lies in the implementation of an innovative strategy centered around collaborations and partnerships with fashion IPs.

As per Schumpeter’s framework, Uniqlo and Tadashi Yanai epitomize true “innovators” and typical “creative destructors”, consistently destructing old structures and perpetually creating new ones. By defying the traditional “impossible triangle” in the fashion industry—offering high-quality and fashionable designs with affordable prices—they’ve made their brand accessible to the masses while still appealing to the elite. Over the past 32 years, Tadashi Yanai has, perhaps even unbeknownst to himself, diligently put into practice all the five innovation types summarized by Schumpeter. Through collaborations with upstream raw material suppliers, globally renowned designers, and creative minds, and engaging diverse circles, including anime and cultural IPs, as well as close cooperation with manufacturing partners in Vietnam, Myanmar, and China, Uniqlo has harnessed the winds of globalization and seized the burgeoning opportunities in the Asian market, particularly in China, achieving contrarian success during Japan's "balance sheet recession". Leveraging innovations in product, technology, market, resource allocation, and organization, Uniqlo has become what it is today in defiance of economic challenges. According to an incomplete tally, spanning from 2013 to 2023, Uniqlo has collaborated with 38 designers, 72 artists, and over 270 cultural or anime IPs, resulting in more than 350+ co-branded collections or individual items. Over this period, from the fiscal year 2013, when sales already reached a remarkable 1.14 trillion yen, to the fiscal year 2023, there has been an astounding nearly 2.5-fold increase in sales and a remarkable 320% growth in profits. The expansion is further exemplified by the progression from 29 domestic stores in Japan in 1991 to a global network of 2,434 stores by 2023. The growth in sales and net profits over these 32 years is truly awe-inspiring. Time, as the witness, reflects Uniqlo's unwavering commitment to innovation. This narrative holds valuable insights and inspiration for Chinese entrepreneurs navigating the challenges of a globalized yet fragmented landscape, coupled with slowing economic growth and intense competition.

In pioneering new markets through innovation, Apple stands out as an excellent representative. While Nokia dominated the traditional mobile phone market, Apple introduced the smartphone, fundamentally revolutionizing the entire industry. In an article titled What would Joseph Schumpeter have made of Apple?, the author argues that Apple embodies many aspects of the concept of “creative destruction” proposed by Schumpeter. Similarly, in the fashion realm, Uniqlo is another outstanding example that demonstrates various features of “creative destruction”. Interestingly, Tadashi Yanai once remarked, “Our competitors are not fast-fashion brands like Gap or ZARA; our competitor is Apple.” Rather than considering them as competitors, it reflects a shared dedication to innovation, a keen understanding and anticipation of consumer needs, and a drive to overturning traditional norms. The two share a strong resemblance and a mutual admiration for their persistent pursuit of innovation.

Uniqlo believes that clothing is not just about fashion but is fundamentally a necessity in life, encapsulated in their philosophy of LifeWear. Breaking it down, it signifies the fusion of “Life” and “Wear”, representing high-quality everyday apparel perfect for daily dressing. What sets Uniqlo apart is its astuteness in elevating design and creativity to the strategic forefront of corporate competition, much like Steve Jobs did. Simultaneously, Uniqlo spares no effort in enhancing product quality, durability, and added value through the innovation of fabric technologies. Similar to the iterative approach of Apple’s iPhones, Uniqlo’s collaborative collections maintain its foundational products' core features and brand style while focusing on upgrading and enriching key technologies and details. Leveraging the influence of renowned designers, Uniqlo enhances brand strength, tapping into markets where both the elite and fashion-conscious consumers are willing to invest. Christophe Lemaire has emphasized the significance of the “KISS principle”, which stands for “Keep it Simple, Stupid”. In his view, excellent products should cater to everyone, whether young individuals immersed in fashion culture or the general public, making products easily understandable and acceptable to all through the simplest intuition. This principle is highly applicable to other industries and brands aspiring to excel in "product innovation".

Regarding collaborations with globally renowned designers, Yukihiro Katsuta, Group Senior Executive Officer at Fast Retailing and Head of Global Research and Development at Uniqlo, believes that designers with diverse backgrounds can bring unique perspectives to brand design. He sees the challenge for the brand itself as learning how to understand various ways of thinking and adopting new working methods within the entire system. “We always believe that there is room for improvement, and there are many things we should and can do. Perhaps it’s difficult to achieve solely on our own, and maybe we need more support and need to learn from others. This is why designer collaborations are not just for commercial purposes but also for market goals. It’s an investment in the company’s future.”(4)

Uniqlo is not alone on the journey of innovation and creative destruction. There are other industry players also adopting similar innovative strategies and consistently experiencing growth. Some notable examples include Nike, born in Portland, USA, in 1972; Decathlon, founded in France in 1976; Crocs, born in America in 2002 and turned into a global sensation with its “ugly clogs"; Moncler, founded in France in 1952 and acquired by Italian entrepreneur Remo Ruffini in 2003; UGG, founded in 1978 in Southern California and later acquired by Deckers in 1995…This trend is even more pronounced in the luxury industry, where the importance of creativity, innovation, and collaboration cannot be overstated. Over the past decade, many luxury brands have appointed non-traditionally trained creative directors, engaging in diverse collaborations with trendsetting brands, contemporary artists, pop culture icons, local cultures & intangible cultural heritage, digital technologies, and the metaverse. Noteworthy mentions include Louis Vuitton, Dior, Gucci, Balenciaga, Fendi, Bvlgari, Tiffany&Co., Prada, Miu Miu, Loewe, and others. However, the proliferation of such collaborations raises a question: when innovation itself loses its novelty, it becomes a call for fresh waves of innovation and creative destruction to break through the old equilibrium or monopoly.

Tadashi Yanai’s office hangs a piece of calligraphy that reads, “Success often comes during tough times, while failure arises from arrogance.” He mentions that Sam Walton’s Made in America and Peter Drucker’s Innovation and Entrepreneurship have had a deep and lasting impact on him. (5)

Anyone who acknowledges innovation as the fundamental driving force of economic development can be referred to as a “Schumpeterian”. In this sense, Tadashi Yanai and his fellow explorers may well be considered as such. Through his own experiences and achievements, he has exemplified the integration of theories and practices, demonstrating how Uniqlo can navigate the cycles and achieve rejuvenation and growth amidst Japan’s “Lost 30 Years” through Schumpeter’s principles of product innovation, technological innovation, market innovation, and organizational innovation. This has allowed Uniqlo to surpass American brand Gap and catch up with H&M from Sweden and ZARA from Spain, with the ultimate goal of becoming the world’s number one brand. However, despite this success, Tadashi Yanai humbly refers to it as “One Win, Nine Failures”.

Understanding this perspective holds practical relevance for our present day.

References:

(1)/(2). “Why Are Innovators Considered Schumpeterians?” - LatePost

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/FJF1SEvk1zsEbo42olTEYQ

“The Theory of Economic Development” by Joseph Schumpeter, translated by Jia Yongmin, China Renmin University Press, 2019 edition, P61.

(3)/(5). “Uniqlo Founder Tadashi Yanai: Running a Business Requires Making Everyone Around Happy” - iBloomberg

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/Ke3ieXV3PUsDsLx-B7_gIg

(4). “Uniqlo’s Plan C” - iBloomberg

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/dg0DpA7IyXGYUYjWzWzKvg

复制成功!